The Workforce Is Even More Divided by Race Than You Think

The labor market is stratified, if not calcified, by race, with whites seeing higher wages and lower unemployment, while blacks and Hispanics cluster in lower-paying jobs.

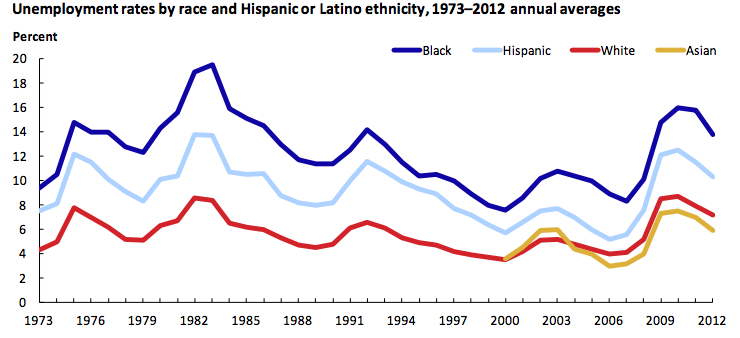

Let's begin with the fact that black unemployment is higher than Hispanic unemployment, which itself is higher than white unemployment. This hasn't just been true for the last year, or the last decade. It's been true for the last four decades and beyond.

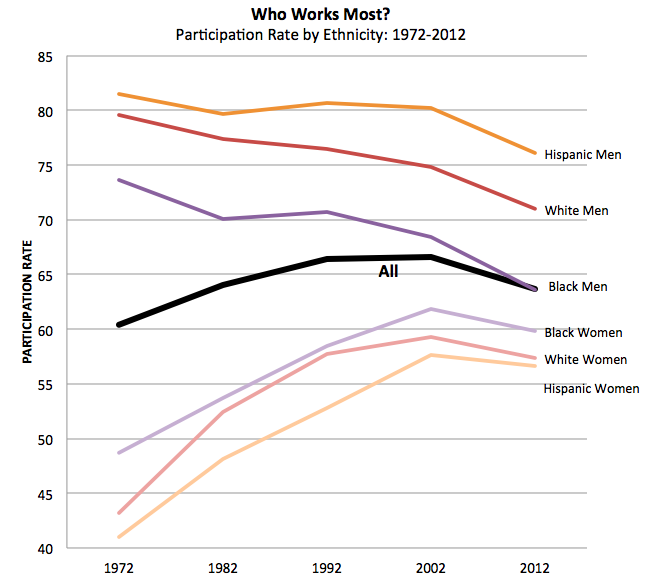

And we'll continue with the fact that, when you look at participation rates over the same 40 years, Hispanic men work more often than white men, who consistently work more than black men. Among women, the trend has been the mirror opposite and just as unchanging. Black women have consistently worked more often than white women, who have consistently worked more often than Hispanic women.

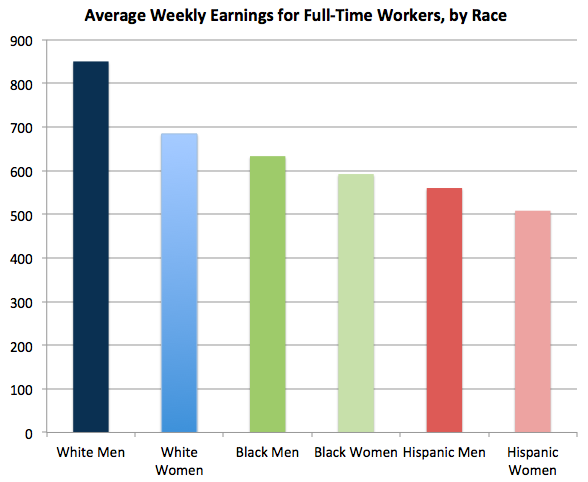

And we'll end with a snapshot of 2012, showing average weekly earnings by race and gender. White men and women out-earn black men and women, who themselves out-earn Hispanic men and women, among full-time workers—even though Hispanic men have the highest participation rate.

The numbers reveal a workforce stratified, if not calcified, by race, with whites seeing higher wages and lower unemployment, while blacks and Hispanics constantly stuck behind them.

According to the BLS, whose data provides the backbone for this piece, the labor economy isn't merely stratified at the macro level. It's stratified at the job-by-job level. Different races and ethnicities cluster in different sectors.

Hispanics, for example, account for about 15 percent of all jobs, but a whopping 36 percent of all high school dropouts. They make up about half of all farm workers and laborers, 44 percent of grounds maintenance workers, and 43 percent of maids and house cleaners. Blacks, who make up just 11 percent of the workforce, account for more than a third of home health aides and about 25 percent of both security guards and bus drivers—rather low paying jobs.

Whites, on the other hand, make up more than 80 percent of the country's workers. But they account for nearly all farm managers and ranchers (96 percent) construction managers (92 percent), carpenters (91 percent), and CEOs (90 percent). The story is true for Asians, as well—not included in these graphs for a lack of historical data. Asian-Americans account for 5 percent of the workforce, but also a whopping 60 percent of personal appearance workers, (e.g. hairdressers, nail salon workers), 29 percent of software developers, and nearly one in five physicians and surgeons.

These figures suggest that at least two separate, simultaneous things are happening. First, it's likely that network effects within racial and ethnic communities have contributed to certain professions having far-above-average concentrations of certain groups. Second, the stratification of work probably suggests that there are underlying education (and family) differences.

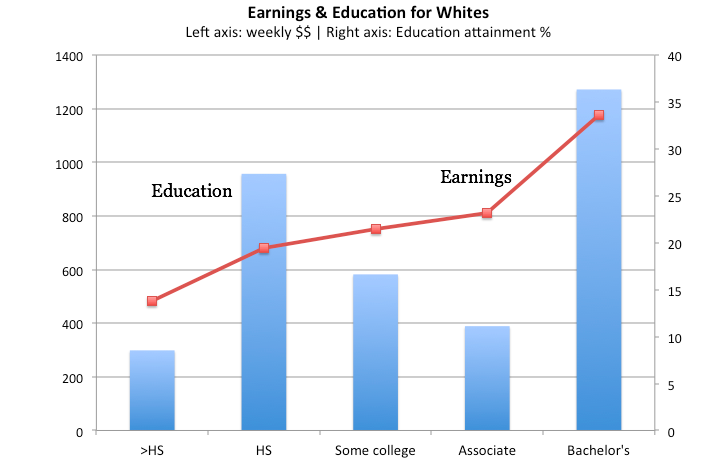

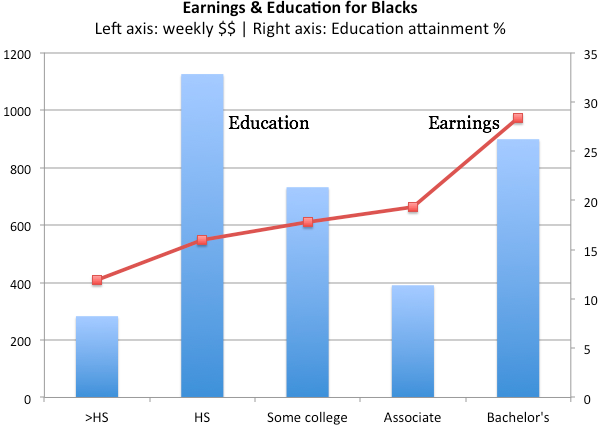

Indeed, every story about earnings is a story about education. So let's tell the education story.

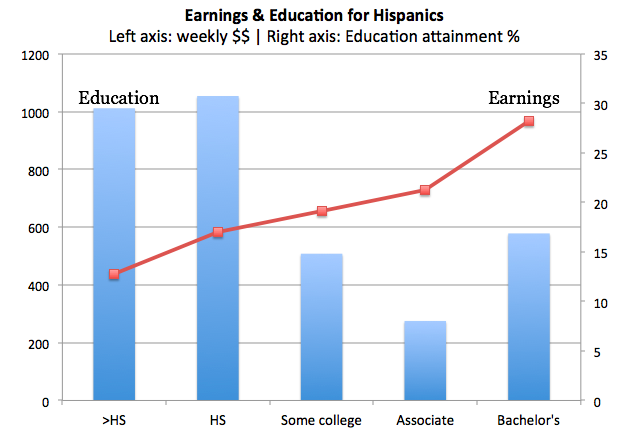

Here are three graphs showing each ethnic group's breakdown of education attainment (in BLUE COLUMNS) vs. their typical earnings at each education level (the RED LINE). Whites, for example, are four times more likely to earn a bachelor's degree than to drop out of high school. Hispanic adults, meanwhile, are almost twice as likely to drop out of high school than earn a bachelor's degree. Here's what they're earning at those levels...

Blacks and Hispanics, who make up about one-quarter of the workforce, represent 44 percent of the country's high school dropouts and just 15 percent of its bachelor's earners. Until we can close the difference between those numbers, it's unlikely that the workforce's unyielding racial stratification will improve.